@evolvable-by-design/pivo v0.0.3

Pivo

An HTTP client to build evolvable-by-design web user interfaces that use RESTful APIs

General Information

- At the moment the project is on GitHub because it is convenient for me to do so

- Readme in progress, I focus on the library at first and will document it when it will be ready to use

- Contributing guide not done yet

- Do not hesitate to get in touch with me for more information

Todo

- Tests

- Support research function

- Make the library way more robust

Why Pivo? The problem statement.

It has become common practice: we use RESTful APIs to access and manipulate data on frontend applications. And to build these frontends, we separate the logic of the view and navigation from the logic that makes the REST API calls. While the logic of the view is materialized through components, the logic of the interactions with the REST API is dispatched into services. For example, all the calls to the Issues on the Github API would be done in an IssueService.

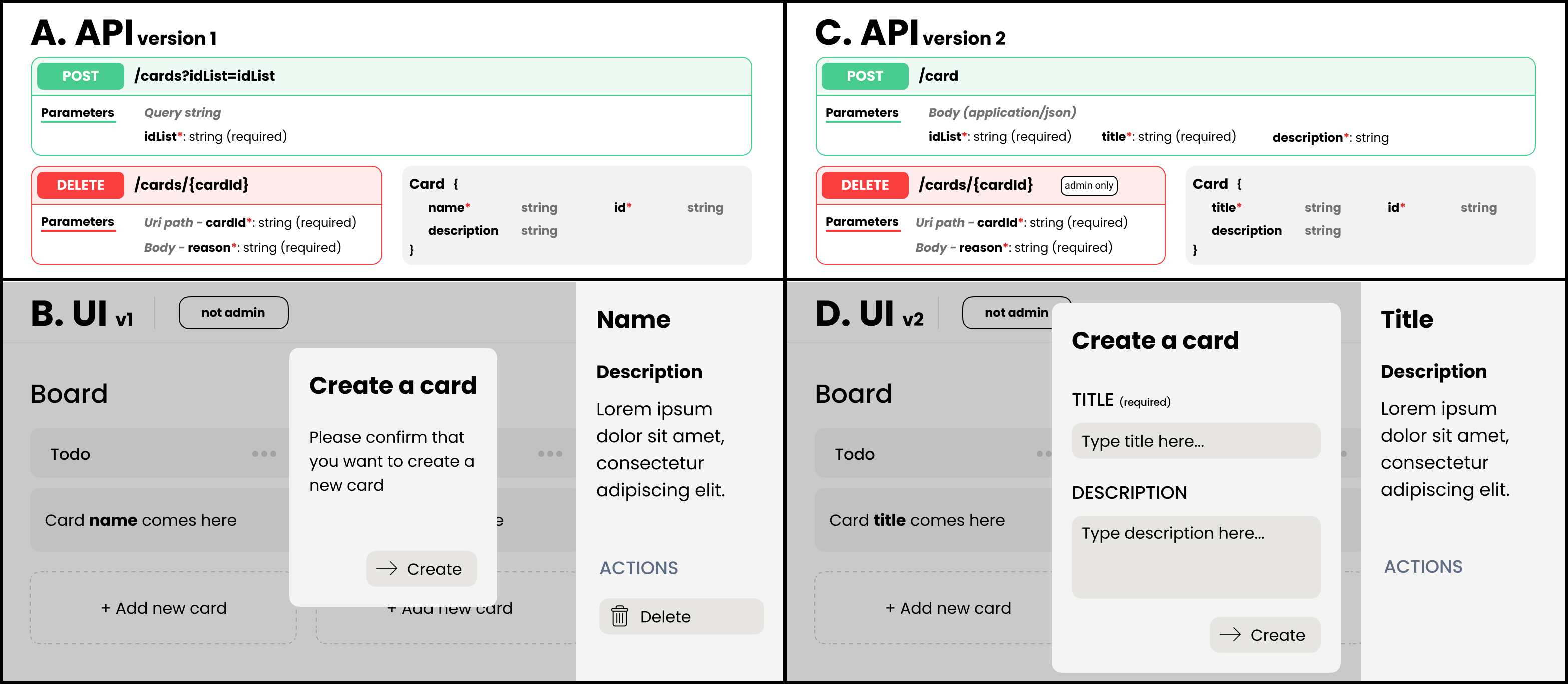

As an example, we consider that we have the following REST API and want to build the following frontend application that is very similar to Trello. Here, we will focus on the components that detail and enable the creation of a card.

With the first version of the API (left part of the above figure), to create a card into a list, a POST request must be sent to /cards?idList={idList}. It would return the created card in the response body. Then, to name and describe the card, another request must be sent to update it after its creation. And to delete it, a DELETE request must be sent to /cards/{cardId} with a JSON object in the body, containing a reason field that the user must input.

To implement the card creation component and mecanism with React, we would write the following code to be compatible with the first version of the API:

const CardCreationComponent = ({ idList }) =>

<div>

<h1>Create a card</h1>

<p>Please confirm that [...]</p>

<button onClick={() => CardService.createCard(idList)}>Create</button>

</div>

class CardService {

function createCard(idList) {

Http.post('/cards?idList=' + idList)

}

}On the other hand, to display the detail of a Card, we would write this code:

const CardDetailsComponent = ({ card }) =>

<right-pane>

<h1>{card.name}</h1>

<h2>Description</h2>

<p>{card.description}</p>

<h2>ACTIONS</h2>

<pop-up-with-button buttonLabel="Delete"

onConfirm={(reason) => CardService.delete(card.id, reason)}>

<input type="text" label="reason" />

</pop-up-with-button>

</right-pane>

class CardService {

function delete(cardId, reason) {

Http.delete({

url: '/cards/' + cardId,

body: { reason }

})

}

}Yes, this code would not work with the second version of the API (right part of the above figure). Indeed, it would:

- send the request to the wrong URI (

/cardsinstead of/card) - incorrectly send the

idListthat should now be sent into the request body instead of URL. Thus, the REST API would not find it - not send the required

titleparameter to create a card, because this is an addition in v2 - not hide the delete button when the user is not an admin

- be unable to display the title of a Card, because it looks for

card.nameand notcard.title

As a consequence, the code of the frontend have to be maintained to ensure that it will not break. Unfortunately, this task is no fun, time-consuming and error prone.

Concretely, the changes to do are:

Http.post('/cards?idList=' + idList)->Http.post('/card', body)- Move the

idListparameter ofcreateCardto the body:Http.post('/cards?idList=' + idList)->Http.post('/card', { body }) - Add a form to the

CardCreationComponentin order to let the user input thetitleanddescriptionparameters. In addition, update the createCard function signature fromfunction createCard(idList)tofunction createCard(idList, title, description)and finally send the three parameters in the request body:Http.post('/card', { idList, title, description }) - Update the view to verify the user's permission. So, first the component should get access to the user profile and then a condition must test his access rights.

- Replace all

card.namebycard.title

Among the changes that require to update the code, we distinguish the changes to:

- An URI schema

- The parameters of an operation

- The response data schema

- Access rights and business rules

- The deletion of elements

We give a more detailed taxonomy of API changes on our Gitbook.

Pivo proposition

Instead of writing such likely-to-break code, we propose you to write code that will not break when the API evolve. Then, you might wonder what it looks like?

Going back to the previous example, we propose to write the following code on the frontend to create a card:

const CardCreationComponent = ({ idList }) => {

const createCardOperation = CardService.getCreateCardOperation(idList)

return <div>

<h1>Create a card</h1>

<form generateInputsFor={createCardOperation.parametersSchema} />

<button onClick={(formValues) => createCardOperation.invoke(formValues)}>Create</button>

</div>

}

class CardService {

apiDocumentation = fetchLatestApiDocumentation()

function getCreateCardOperation(idList) {

const parameters = { '/docs/dictionary#listId': idList }

return this.apiDocumentation

.findOperationThat('/docs/dictionary#createCard')

.withDefaultParameters(parameters)

}

}Hence, you can notice three major differencies:

- The HTTP request (URL and parameters) is built within the api documentation class (line 6), to ensure it is compliant with the latest version of the API.

- Operations and parameters are identified by machine-interpretable semantics (see OWL) instead of ambiguous keywords (line 14 & 16), to enable the api documentation class to read the api documentation and make sense of it.

- The form to let the user input the operations' parameter value is generated by the frontend based on the operation schema retrieved in the api documentation. Combined with 1 it ensures that all parameters will be sent to the API in the expected format.

These differencies enable the implementation of frontend applications that do not break when the API evolves. We qualify such kind as frontends of being evolvable-by-design.

To enable this, a documentation of the REST API must be available to the frontend. With Pivo, it must be documented with OpenApi and enriched with OWL semantic descriptors. These two steps can be done by the API provider or by anyone else. The typescript community does a similar thing by typing existing libraries and sharing these types within the @types repository.

Accordingly, to display the detail of a Card, we propose to write the following code:

const evolvable = new EvolvableByDesignLib(fetchLatestApiDocumentation())

const DELETE_SEMANTICS = '/dictionary#deleteAction' // OWL

// Type of the card param below: SemanticData

// SemanticData is custom to the library

// It maps the data from the API to the semantic descriptors found in the documentation

function showCardDetailsComponent ({ card }) {

return (

<right-pane>

<h1>{evolvable.get('/dictionary#name').of(card)}</h1>

// Description and actions heading

<if test={evolvable.isOperationAvailable(DELETE_SEMANTICS).on(card)}>

<pop-up-with-button

buttonLabel='Delete'

formSchema={evolvable.getOperationSchema(DELETE_SEMANTICS).of(card)}

onConfirm={formValues =>

CardService.delete(card, formValues, approach)

}

/>

</if>

</right-pane>

)

}

class CardService {

static delete (card, userInputs, evolvable) {

evolvable

.invokeOperation(DELETE_SEMANTICS)

.on(card)

.with(userInputs)

}

}Again, it uses machine-interpretable semantics to identify data in order to display the proper data to the user. So, a change of the keyword used in the API response does not break the frontend.

Also, the card instance has been enriched with information from the API documentation and hypermedia controls added to the API response. This is a requirement of this approach that we discuss later. Thus, this additional information is leveraged to test the availability of the delete operation. Also, to invoke it when the user clicks the delete button. Thanks to this mecanism, all access rights and business rules can be removed from the frontend. Hence, the developer can focus on visual logic code and user experience.

Apart from writing the frontend application slightly differently, as we just show you, two things are required from the API. First, a documentation of the API must be available and it must comply with some requirements that we detail in the API compliance guide. Second, the API must send hypermedia controls in the response body. This is also detailed in the API compliance guide.